A blog post in The New York Times online recently addressed this issue noting, "Definition of Cancer Should Be Tightened, Scientists Say."

Here's a typical scenario: We've had a screening test for some form of the illness many of us fear the most (actually, I fear Alzheimer Disease at least as much). Then we hear the words, the really scary ones. "You've got cancer." We may not hear the modifiers that come before the C word, or anything else that follows. The National Cancer Institute's (NCI) working group wants to clarify that some conditions are pre-malignant (they're not cancer yet and, in certain cases, may never become carcinomas {another term for cancer}).

I want to return to the JAMA preprint article I mentioned in my last post; it's titled "Overdiagnosis and Overtreatment in Cancer? An Opportunity for Improvement"

The group focused on cancer screening to include breast, lung, thyroid, colon, cervix, melanoma and prostate exams. They tracked the incidence of a variety of cancers over the thirty-five-year period from 1975 to 2010 and found three different result patterns have been noted as more and more of us are screened for more and more conditions.

Some cancers have been diagnosed somewhat more frequently, but in many cases are less serious variants, less likely to kill us, so, overall, they are causing fewer deaths. Other malignancies are being found less frequently (due to improved and/or more frequent screening resulting in precancerous stages being treated) and the death rate from them has gone down considerably. And some cancers are being diagnosed much more often, but much of that increment is what the researchers termed "indolent disease," less active or progressive disease and overall their death rate is nearly unchanged or increased much less than the percentage change of their being diagnosed would indicate.

Let's take cancer of the prostate for an example of the first group. The incidence (rate of occurrence) in cases per 100,000 men has gone from 94 to 145.12, a fifty-four percent increase, while the death rate from the disease has gone down 30%.

So we're doing better with treating this form of cancer, seeing a lower mortality rate, but we're discovering considerably more cases that are not causing deaths. As I said in my last post, I've decided not to have any more PSA tests; at my age (72), other things are much more likely to kill me than prostate cancer. I clearly would have made the opposite choice (and did) at age 45 or 55.

The other tumor in the first group is breast cancer. Mammography has certainly become more of a routine procedure looking for breast lumps, but while the incidence of breast lesions has gone up 20% in the thirty-five year interval the NCI group looked at, the death rate has fallen by 30%. Much of that is due to what is termed adjuvant therapy, e.g., chemotherapy following surgery.

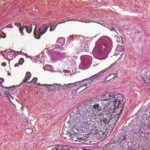

But another group of women with a positive mammogram have a less serious form of disease called ductal carcinoma in situ. The NCI webpage on this tumor says it is noninvasive, but some (uncertain) percentage of these can progress to an invasive form.

What is DCIS? It's the most common type of non-invasive breast cancer, starts in the milk Ducts, has been termed a Carcinoma and is In Situ which means "in its original place."

The NCI group who published the JAMA article terms it a premalignant condition and would prefer it not be called a carcinoma. Most of these lesions are small (~70% are less than 1 cm in size) and 80% are not found by breast examination, but show up on a mammogram.

Another NCI group, however, reviewed the medical literature on DCIS saying until recently the usual response to its discovery was a mastectomy. More recently there have been two randomized, controlled trials of breast-conserving surgery (lumpectomy) combined with radiation therapy and even more recently a double-blind prospective trial utilizing chemotherapy with the drug tamoxifen given daily for 5 years in addition to lumpectomy and radiation.

A control group had the surgery and radiation plus a placebo. The group that got tamoxifen did considerably better and other clinical trials are in progress.

The second group of tumors included colon cancer and cervical cancer. The statistics are fascinating. For colon cancer the incidence rate has gone down 31% and the death rate 45% and the trend is quite similar for cancer of the cervix (5 and 59% decrements)

We all have a colon, so let me focus on that cancer for a moment with a recent personal vignette.

My father had a large sessile polyp, a projecting growth without a stalk, in the very first part of his colon. It was initially benign, would have been difficult to remove and he was in his late 70s. so it was repeatedly observed and biopsied. Eventually it had a superficial layer that was cancerous. By then he was nearly ninety and the decision was to shave off layers until what was left was benign.

So that gives me a positive family history of colon cancer.

My previous colonoscopy (2006) was totally negative and without that family history my gastroenterologist would have said, "Come back in ten years."

Because of Dad's polyp, my GI doc wanted me back in seven years. And he was right; this time I had three small polyps, all of them benign and all on stalks (The technical term is pedunculated.), making them easy to snip off. I had decided to stay awake and watch and the procedure, while somewhat uncomfortable, was fascinating. I went home reasonably confident that my polyps were benign.

But there are three kinds of those colon polyps, according to the followup letter I received. Type one is of "minimal clinical significance." Type two, which I had, is benign, but potentially precancerous. Early colon cancer screening for first-degree relatives is recommended. It was suggested I speak to parent (both dead), siblings (my only sib died at fifty-seven) and children (my daughter), so they can discuss colon cancer screening with their physician.

I copied the letter to bring to my daughter on a vacation trip we're taking.

Type three is also benign, but there's considerably more chance of it turning into a cancer.

So my next colonoscopy will be in five years this time.

If I had a totally normal colon at age 72, my GI doc had said he'd not suggest any more colonoscopies ever. My routine ten-year-interval next one would have been at age eighty-two and that, he felt, is too old to screen someone whose seventy-two-year-old colon was negative for any polyps.

But with their natural history of being potentially precancerous, the discovery of types two or three leads to a change in schedule and a family search is quite reasonable.

And, I take it, that's why the incidence of colon cancer and the death rate from that malignancy have gone down over that thirty-five-year period. There's presumably been better treatments developed for those who do end up with that form of cancer, but by dong colonoscopies and removing pre-cancerous lesions (i.e., polyps), we're preventing many of them from altering into malignant tumors.

So those are examples of the group of tumors that are being discovered more often, but are causing fewer deaths and of one (colon cancer) that our screening is helping prevent.

I'll write about cancer of the cervix and of thyroid cancer and melanomas next time.