Rabies is a viral disease affecting the brain and spinal cord, affecting warm-blooded mammals, passed to humans (the technical term is a zoonotic disease), with rare exceptions, via an animal bite , and, except for a very few recent cases, uniformly fatal in mankind.

It's an ancient disease with written descriptions going back 4,000 years. A Codex (an early form of a book with individual handwritten pages on papyrus or vellum) in Mesopotamia described canine rabies ~3,400 years ago, but a timeline on the disease mentions dog owners in a Babylonian city being fined if their animal's bites caused death, presumably from rabies, nearly a thousand years before that.

In 1271 CE, rabid wolves in what is now Germany caused 30 deaths by attacking villagers. The disease was first reported in the Western Hemisphere in 1703 and caused canine rabies in Virginia in 1753.

In France, Louis Pasteur and a colleague, Emile Roux, started to work on a a vaccine for rabies in 1881. Roux made a candidate vaccine two years later using the spinal cord of an infected animal. In 1885 Pasteur, who was a chemist, not a physician, gave the vaccine to a nine-year-old child who had multiple deep bites by a rabid dog, saving his life. Over the next few years he inoculated over 700 people with only one failure (presumably a case where the virus had already reached the central nervous system). Donations helped start the institute named after him and rabies vaccination was launched widely.

Rabies in the United States has become a rare entity; we used to have more than a hundred case a year, but that fell to one to three each year by the 1990s. Previously one heard of rabid dogs; now, at a cost of over $300 million per year, an extensive vaccination program for companion animals has marked diminished their incidence, animal control programs are in place and rabies labs are maintained. Post exposure prophylaxis (PEP) used to involve a painful series of shots in the abdominal wall; newer protocols have been developed that are much less fearful.

We used to have to vaccinate our dogs every year and couldn't get a city/county tag for them without proof of vaccination. Now a three-year canine vaccine is available. Since 1990 more cats than dogs have been found to be infected with rabies in the United States.

In the rest of the world rabies kills roughly 55,000 people every year with the vast majority of cases (95%) occurring in Africa and Asia. Almost all (97%) of those deaths start with a dog bite. India is "rabies central" with 20,000 cases a year. A 2001 law forbade the killing of dogs and Mumbai alone reported 80,000 people bitten by dogs in 2011. Strays survive on mounds of garbage, but Hindus oppose the killing of many kinds of animals. Scientists there are working on a canine contraceptive vaccine.

On the other hand Australia and Japan have eliminated rabies carried by terrestrial animals.

Here rabies is carried, not by dogs, but by bats (found in many parts of the country), raccoons in the eastern US, skunks in the north and south-central states (sometimes in the East), foxes in western Alaska and parts of Arizona and Texas as well as the East, and previously coyotes in the southern parts of Texas. Rabbits, rodents and hares rarely get the disease and haven't been known to pass it to humans in the United States. Both raccoons and squirrels may carry a roundworm parasite that can be passed to humans and imitate rabies.

Opossums have a behavior to scare away predators (drooling, hissing and swaying), but are quite resistant to rabies.

In 2013 four Colorado livestock have been found to be infected with rabies, the most recent being a bull In Weld County a few miles to the east of where we live. The suspicion is a rabid skunk bit the bull. And in my county, where skunks exceed bats as the most common rabies carrier species, three adults and five children were recently bitten or scratched by a rapid kitten and got post-exposure prophylaxis.

I called a friend who has Shire (and other) horses, dogs and barn cats and she told me her son killed the seventh rabid skunk in the county several years back; since then all their animals have been vaccinated. She was aware that rabies vaccination is required at horse shows in some parts of the United States and at least four eastern states strongly recommend it for all horses. A 2008 Colorado State University online discussion of whether to vaccinate horses here mentions the sharp shift from bats to skunks as the common carrier species. Rabies here has also been found in raccoons, foxes and bison.

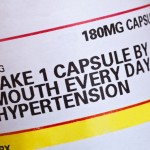

The World Health Organization, commonly known as WHO, has online recommendations for post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP). The administration of PEP should be prompt and local to the bite site, in an attempt to prevent the virus from migrating along nerves to the brain. In 2010 the PEP procedure was altered in the United States with one fewer dose of the vaccine being given.

Wound cleansing is crucial in rabies prevention. Animal studies have shown thorough attention to the wound markedly reduces the likelihood of rabies. For those who are not immunosuppressed and have not previously gotten PEP ( or been vaccinated because of high risk: e.g., veterinarians, spelunkers, international travelers to places where rabies is common), one dose of rabies immune globulin and four doses of rabies vaccine are given over a two-week period.

Survival from rabies wasn't reported until recently.

In 2004 an adolescent American girl developed rabies (after handling a bat and being bitten by it), was placed into an induced coma and received a variety of medications to temporarily suspend brain function and fight the virus. She survived, graduated from college in 2011 and has a 2013 website describing her illness. The "Milwaukee protocol," first tried in her and subsequently modified, has now been used on a total of forty-one other rabies patients worldwide with one source saying five survived.

The care involved is detailed and incredibly expensive; one report says $700,000 was spent in a futile attempt to save one patient.

I'd certainly get PEP after a bite if the animal involved had rabies. However, that's not always obvious, even in bats; a recent study at the University of Calgary found roughly one percent of bats sampled had the virus. A comment from the report was that bats seldom come in contact with humans, so I think those that do in unusual settings should be suspect.

So vaccinate your animals and be wary of any with abnormal behavior.