I've covered this territory before in a prior post, but there's compelling new data on this crucial health issue. In the June 19, 2013 edition of JAMA is an article titled "Time to Treatment With Intravenous Tissue Plasminogen Activator and Outcome From Acute Ischemic Stroke." The basic concept is that promptly getting someone who has suffered a stroke to a hospital that has modern "clot buster" therapy available markedly improves their outcome.

But in order to understand what it is that the research paper espouses, let's go back a few notches and work up gradually to the details of the paper.

I've always wondered why a stroke is called, in lay language, a stroke (physicians call it a CVA, a cardiovascular accident). The best answer I've seen is that someone who appeared to be in generally good health could abruptly be struck with acute neurologic symptoms: sudden weakness or numbness on one side of the body; sudden confusion, difficulty speaking or understanding; sudden loss of vision in one or both eyes; sudden motor problems (difficulty with walking, balance, loss or coordination or dizziness); or sudden severe headache without any known cause.

Most people (93%) recognize the first of those symptoms, the sudden onset of unilateral weakness or numbness, as indicative of a stroke, but less than 40% know all five major signs that a CVA is in progress. When you have one of the five, the CDC says you should call 911. You need to be at the Emergency Room within a realtively brief period of time to have an optimal chance of a best-outcome recovery.

The major risk factors for stroke are high blood pressure, high LDL cholesterol and smoking. The Stanford online article on CVAs mentions that all the usual cardiovascular threats can play a role, e.g., diabetes, obesity, lack of exercise, diet, stress. Oral contraceptives, especially those with higher estrogen content appear to increase the risk of blood clots, including those that may cause a strokes, particularly in women over 30 and post-menopausal estrogen use may somewhat elevate stroke risk.

Of course you can't change your age (some try) and two-thirds of strokes occur in those over 65. It's also about 25% more common in males and a positive family history of CVAs may be a factor. African Americans have twice the risk of having a first stroke as do whites.

The first more detailed accounts of stroke, referred to as apoplexy from the Greek word ποπληξία, meaning struck down with violence, were written by Hippocrates (460 to 370 BCE) describing a sudden collapse, a loss of consciousness and paralysis.

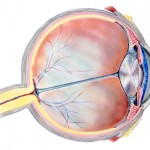

The American Stroke Association has a great visual on types of strokes, listing three kinds: ischemic (lack of blood flow to the brain), hemorrhagic (the result of bleeding in that vital area of our bodies) and TIA (transient ischemic attack, a mini-stroke or warning stroke), but I also went to the online information sheets from the Stanford Stroke Center which has a comprehensive discussion of the ailment.

A stroke is sometimes called a "brain attack," presumably to underline its importance as equivalent to a heart attack . It is a leading cause of death in the United States, killing one of us in this country every 4 minutes and costing nearly $40 billion a year between health care, medications and missed work days.

Nearly 800,000 of us will have a stroke this year and 87% of all CVAs are of the ischemic type. As I've said before, "Time is Brain." You can lose 2 million brain cells every minute after the onset of a stroke.

Although the average age in large studies of CVAs is in the early 70s (actually 72, the age I'm at now), one third of all stroke victims are under the age of 65.

Prior studies with a protein called tissue plasminogen activator, a substance that can dissolve blot clots (and therefore termed a clot buster) have shown the possibility of minimizing damage from an ischemic stroke, but have been limited in size and therefore not having results as clear-cut as I wanted to see.

Now that limitation has been overcome by a very large-scale data set, the US national "Get With The Guidelines--Stroke (GWTG-Stroke) study. This is a combined project of the American Heart Association and the American Stroke Association, started in 2003 and involving 1,656 hospitals and over 2 million patents.

The JAMA article, looking at results of clot buster therapy in over 58,000 patients who had an ischemic stroke and got treatment in less than four and a half hours, had striking conclusions.Every 15 minutes slower from onset of symptoms to treatment worsened the eventual outcome.

Let's flip that around: the quicker you get to the ER the better are your chances of having a good result.

That means fewer deaths, fewer brain hemorrhages, better likelihood of walking by yourself and better chance you'll go home instead of to a nursing home.

It didn't matter what your age, gender or race/ethnicity was, the results were similar in all groups.

So remember (or learn) the five major symptoms: sudden weakness or numbness on one side of the body; sudden confusion, difficulty speaking or understanding, sudden loss of vision in one or both eyes, sudden motor problems (difficulty with walking, balance, loss or coordination or dizziness) or sudden severe headache without any known cause.

And if you have one of them, call 911 and get your brain to an ER by ambulance.

Bring the rest of you along to keep it company.