I was reading the July 3, 2013 edition of JAMA and came across an article and an editorial on better ways to manage elevated blood pressure (BP). The basic concept stems from data reviewed by the CDC in a 2012 online publication: high BP, AKA hypertension, is a major risk factor for both stroke and cardiovascular disease which jointly are the number one causes of preventable death in the United States.

Do you know what your BP is? Let's start from scratch with the kind of numbers you might hear about when you see your doctor or have your BP checked in other settings (e.g., the grocery store we usually shop at has a free automated system for BP measurement).

My BP usually runs about 116/ 68, but, similar to yours and everyone else's, my BP varies from those numbers from minute to minute. The top number, called my systolic pressure is always higher than the lower (diastolic pressure) It measures pressure in my arteries when my heart contracts (beats) while the bottom number measures it between heart beats when that muscular organ is resting and refilling with blood about to be pumped out to the rest of my body. The American Heart Association has a nice webpage explaining BP.

I'd like to see BPs under 120/80 and that seems to be a reasonable consensus figure in articles I read. Hypertension (HTN) is conventionally defined as a BP higher than 140/90 and the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute's website calls any BP between 120/80 and 140/90 prehypertension. That's new to me, as the designation used to be applied to those with BPs between 130 and 139 for the upper number and 85 to 90 for the lower one. But I retired in 1998 and the BP goals changed in 2003.

My 2006 copy of Kaplan's Clinical Hypertension, the ninth edition of this amazing, mostly one-person work by a senior professor in Dallas (I just ordered a used copy of the 2010 tenth edition), mentions that 120-129/80-84 used to be considered normal and 130-139/85-89 was thought to be borderline. But the 2003 report of the Seventh Joint National Committee put BPs anywhere over 120/80 into the new category saying it wasn't a disease, but a designation to identify those at high risk of developing hypertension.

So what if one of your numbers is in this range, but not the other? The Harvard Medical School's Family Health Guide article on prehypertension notes that BPs vary from time to time and from arm to arm. If you have BP numbers over 120/80, the classification will depend on your average/usual readings, not the extremes. They suggest you always use the systolic or diastolic number that puts you in a higher category (normal, prehypertension, hypertension). So, for example, if your average is 124/76 or 118/83, you're in the prehypertensive group

The CDC paper and others say the overall prevalence (i.e., the proportion of a population having a disease) of HTN in America is ~30%, but that increases with age with many estimates stating it's 70% in those of us 65 and older. That group is more prone to systolic HTN with only the upper number being elevated. That's still high BP and dangerous.

Treatment of HTN with diet, weight control and meds is associated with considerable decreases in the dire consequences of uncontrolled HTN: strokes, heart attacks and congestive heart failure (a condition where your heart can't pump out enough blood to keep up with the needs of your body).

All of us should be screened for HTN, even if our BP is less than 120/80. Screening intervals should be at least every two years for those with normal BP and every year for people with prehypertension. Your physician will also consider your other risk factors (weight, age, gender, your blood lipid levels {e.g., total cholesterol, HDL and LDL levels} presence or absence of diabetes, heart disease or chronic kidney disease, exercise patterns) and may, in some case recommend drug therapy even if your BP is <140/80. That's especially likely for those with any of the three chronic diseases I just mentioned.

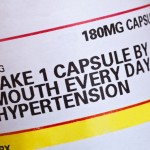

So do we all need to be on medications if our BP is >140/80 (no, your physician may start with non-pharmacologic modalities such as cutting our salt intake) and if we do start on BP meds how often do we need to see our doc? After all, they're really busy these days and we may not be able to get an appointment for several months.

Let me start with my own experience (in the "Dark Ages") and then come up to the present.

When I was in my first Air Force assignment at Langley AFB, VA from 1970 to 1972, I set up a HTN clinic run by a public health nurse, an RN with extras training who didn't want to be a ward nurse. My immediate boss was a cardiologist and, after I set up protocols (e.g., which meds to start with, appropriate followup intervals for various levels of BP, when to call for help), our nurse felt quite comfortable running the BP clinic.

She didn't see other kinds of patients, got very savvy about HTN, read a lot of the current medical literature on the subject, was entirely at ease with calling either of her two consultants whenever she had a question and our HTN patient population could easily get appointments in her clinic.

Fast forward ~forty years.

In 2011 a Veterans Administration group from Durham (coincidentally a place I worked when I was a resident and nephrology fellow at Duke) published an article in the Archives of Internal Medicine (now called JAMA Internal Medicine). Its title was "Home Blood Pressure Management and Improved Blood Pressure Control: Results From A Randomized Controlled Trial."

In brief they followed nearly 600 HTN patients who were randomized into one of four groups. The first had usual care, i.e., being seen in a primary care clinic at intervals. The other three groups involved nurses who administered behavioral management concepts, worked with docs on medication management or did both. The patients had their BPs monitored at home with data transmitted to the researchers. Incidentally 48% of the patients involved were African American.

Overall the research group felt the intervention effects were moderate, but those patients who started with the worst BP control had much better resultant effects.

Now there's the new JAMA article, "Effect of Home Blood pressure Telemonitoring and Pharmacist Management on Blood pressure Control: A Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial." Researchers associated with an integrated health system in Minnesota using electronic medical records, noting that typically only half of HTN patients have adequately controlled BPs, followed 450 patients, roughly half of whom got usual care. The other half got home BP telemonitoring and had PhD pharmacologists following their data and making changes in their BP meds by a protocol worked out with physicians.

BP control was better in the latter group at 6 and 12 months and was even better 6 months after the year-long study ended.

Lesson one: other healthcare professionals can manage HTN. Lesson: doing this via home BP measurements may be the path of the future.