In 1969 President Nixon, prodded repeated by the Harvard biologist Matthew Meselson, decided to end all United States offensive biological warfare (BW) research. The story is told in detail in Volume III of the National Security Archive; the concept eventually led to the 1972 Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention, signed by more than one hundred nations.

Our BW research scientists were very unhappy with the decision and thought some countries, especially the Soviet Union, would not adhere to the treaty at all; they were eventually proven to be right. Our CIA apparently kept a "small" amount of various infectious agents and toxins including 100 grams of anthrax.

In April 1979 the most lethal anthrax epidemic to date began to unfold near the Denver-sized city of Sverdlovsk in Russia. The winds were blowing in a fortunate direction, so only 68 people died; otherwise the casualties would have likely numbered in the hundreds of thousands. Russia said nothing about the incident.

In late 1979 and early 1980 a Russian-language newspaper published in West Germany reported an explosion at a military installation near Sverdlovsk and estimated a thousand resultant deaths from anthrax. Our April, 1979, satellite images were reviewed and roadblocks and decontamination trucks were noted in that area in the spring of 1979.

The Russians, in a March 1980 article, denied this was anything other than a naturally occurring outbreak. Later they claimed any deaths resulted from consumption of meat from anthrax-contaminated cattle and that veterinarians had reported deaths in animals before any human casualties. Dr Meselson arranged a 1988 meeting with Soviet scientists and was convinced that the tainted-meat explanation was plausible.

Finally in 1991, after the Soviet Union broke up and Boris Yeltsin headed Russia, he told President Bush that the KGB and Soviet military had lied. Apparently a technician at the BW plant had neglected to place a filter correctly; the result was a plume of anthrax spores. The Russians shut down the Sverdlovsk plant, only to build a larger one in Kazakastan.

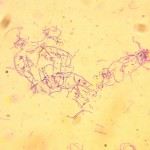

October, 2001, brought an anthrax attack to the United States. A sixty-three-year-old man living in Florida was taken to his local emergency department, confused, vomiting and having an elevated temperature. An alert infectious disease consultant considered the possibility of anthrax after a spinal tap revealed both white cells and the typical bacilli. A prompt response and rapid escalation of information ensued and the bacterium was found in the patient's workplace. Subsequently a history of the victim having examined a powder-containing letter was obtained from his co-workers. Other letters arrived at political and media targets in four states and Washington, DC.

Fast forward to 2010. The FBI finished its eight-year investigation, saying a US biologist who committed suicide in 2008 had been solely responsible for the 2001 bioterroism attack. The man implicated had worked at the Army laboratory at Fort Detrick and the Justice Department concluded he alone mailed the anthrax letters which killed five people, sickened seventeen others and led to a multi-billion-dollar, terror-laced response.

An October, 2011, article in USA Today said each FBI field office now has personnel dedicated to investigate biological attacks, while the bureau itself has an entire major section for counterterrorism: biological, chemical or radiological.

The same infectious disease expert involved in the uncovering of the 2001 letter attacks wrote a followup article published in January 2012 in the Annals of Internal Medicine. He mentioned the initial victim, a photo editor for a supermarket tabloid newspaper, was the 19th known case of inhalational anthrax in the US since 1900 and the first since 1976. Each of the other patients' exposure was directly associated with their work in mills or labs.

One other piece of irony was a Canadian study of anthrax published in September 2001 showing even unopened envelopes containing anthrax spores were a threat. The results had been emailed to our CDC on October 4, 2001, but the message was never opened.